Understanding the Central American Refugee Crisis

In the spring and summer of 2014, tens of thousands of women and unaccompanied children from Central America journeyed to the United States seeking asylum. The increase of asylum-seekers, primarily from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala—the countries making up the “Northern Triangle” region—was characterized by President Obama as a “humanitarian crisis.” The situation garnered widespread congressional and media attention, much of it speculating about the cause of the increase and suggesting U.S. responses.

Faced with the increase of Central Americans presenting themselves at the United States’ southwest border seeking asylum, President Obama and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), specifically, implemented an “aggressive deterrence strategy.” A media campaign was launched in Central America highlighting the risks involved with migration and the consequences of illegal immigration. DHS also dramatically increased the detention of women and children awaiting their asylum hearings, rather than release on bond. Finally, the U.S. government publicly supported increased immigration enforcement measures central to the Mexican government’s Southern Border Program that was launched in July of 2014. Together, these policies functioned to “send a message” to Central Americans that the trip to the United States was not worth the risk, and they would be better off staying put.

Yet the underlying assumption that greater knowledge of migration dangers would effectively deter Central Americans from trying to cross the U.S. border remains largely untested. This report aims to investigate this assumption and answer two related questions: “What motivates Central Americans to consider migration?” and “What did Central Americans know about the risks involved in migrating to the United States in August 2014?”

An analysis of data from a survey of Northern Triangle residents conducted in the spring of 2014 by Vanderbilt University’s Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) reveals that respondents were more likely to have intentions to migrate if they had been victims of one or more crimes in the previous year. In a separate LAPOP survey of residents of selected municipalities across Honduras, carried out in late July and early August of 2014, we find that a substantial majority of respondents were also well aware of the dangers involved in migration to the United States, including the increased chances of deportation. This widespread awareness among Hondurans of the U.S. immigration climate in the summer of 2014, however, did not have any significant effect on whether or not they intended to migrate.

In sum, though the U.S. media campaigns may have convinced—or reminded—Hondurans, and perhaps their Salvadoran and Guatemalan counterparts, that migration to the United States is dangerous and unlikely to be successful, this knowledge did not seem to play a role in the decision calculus of those considering migration. Rather, we have strong evidence from the surveys in Honduras and El Salvador in particular that one’s direct experience with crime emerges as a critical predictor of one’s emigration intentions.

What these findings suggest is that crime victims are unlikely to be deterred by the Administration’s efforts. Further, we may infer from this analysis of migration intentions that those individuals who do decide to migrate and successfully arrive at the U.S. border are far more likely to fit the profile of refugees than that of economic migrants. Upon arrival, however, they are still subject to the “send a message” policies and practices that are designed to deter others rather than identify and ensure the protection of those fleeing war-like levels of violence.

The Northern Triangle Reality and U.S. Response

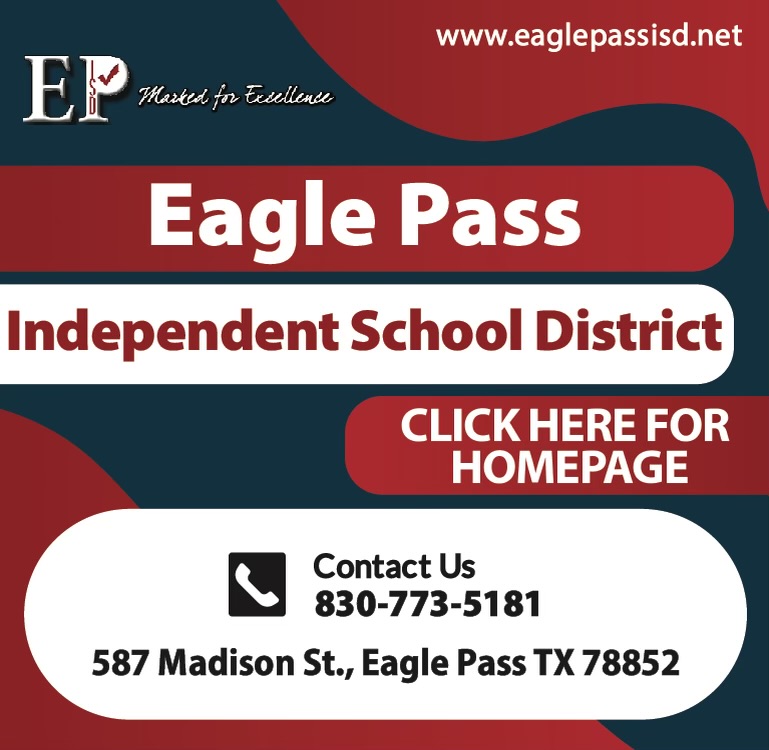

The Northern Triangle region of Central America includes the small, but strikingly violent countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala (Figure 1). Honduras has been recognized as the murder capital of the world for many years, with its homicide rate peaking in 2011 at 91.6 murders per 100,000 people. In 2014, that rate dropped to 66, but remains one of the highest for a non-war zone country. By 2012-13, the rates for Guatemala and El Salvador had dropped as well, but only in Guatemala did this trend of reduced violence continue into 2014-15. Though our United Nations homicide data end in 2013, more recent data from 2015 indicates that homicide rates in Guatemala have remained steady, but have more than doubled in El Salvador. After the late 2013 breakdown of a truce between the country’s two most powerful gangs (MS-13 and Barrio 18), homicide rates increased dramatically, reaching an all-time high of 104 murders per 100,000 people in 2015. Not surprisingly, research on the causes of migration from this region increasingly finds these high levels of crime and violence as a primary push factor in Central American migration.

Figure 1. Homicide Rates for Selected North and Central American Countries, 2000-2013

Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Global Study on Homicide 2013.

DHS itself identified crime and violence, particularly in El Salvador and Honduras, as important factors in the flow of unaccompanied minors leaving these countries for the United States in 2014, concluding that “Salvadoran and Honduran children . . . come from extremely violent regions where they probably perceive the risk of traveling alone to the United States preferable to remaining at home.”

Despite this acknowledgement, the common thread in DHS’ response to the thousands of women and children arriving at the United States’ southwest border in 2014 was to employ a multi-prong deterrence strategy consisting of (a) launching a multimedia public awareness campaign; (b) increasing U.S. assistance to help Mexico secure its southern border region; (c) decreasing the chances of gaining asylum by expediting the removal process; and (d) carrying out raids in January 2016 in search of individuals deemed to have exhausted their asylum claims. These actions were meant to heighten the challenges associated with coming to the United States and ensure that Central Americans knew about them.

In July 2014, the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency within DHS launched the “Dangers Awareness” campaign in the form of billboards, radio, and television advertisements throughout the Northern Triangle countries in order to convince those considering migration that such a trip was not worth the risk. In 2015, these efforts continued under the new name of the “Know the Facts” campaign. The idea was to spread the word among potential migrants that the dangers of such a trip were high and the chances of success were low.

In addition, the United States supported Mexico’s “Southern Border Program” to fortify its southern border. The Southern Border Program is a package of operations implemented by the Mexican government to strengthen security and control human mobility in Mexico’s southern border. According to the Washington Office on Latin America, “Between July 2014 and June 2015, the Mexican government’s apprehensions of Central American migrants increased by 71 percent over the same period in the previous year, before the launch of the Southern Border Program.”

DHS also significantly increased the detention of women and children apprehended at the border who passed the initial stage in the asylum process, referred to as the “credible fear interview,” and were awaiting a full asylum hearing. In the words of DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson, these actions were designed to send a message “to those who are . . . contemplating coming here illegally [that] we will send you back. . . People in Central America should see and will see that if they make this journey and spend several thousand dollars to do that, we will send them back and they will have wasted their money.” Yet, as U.S. District Court Judge James Boasberg noted in his February 2015 ruling regarding DHS detention policy, “Defendants [DHS] have presented little empirical evidence . . . that their detention policy even achieves its only desired effect—i.e., that it actually deters potential immigrants from Central America.”

Finally, in January 2016, DHS deployed a series of raids that targeted Central American families in an effort to accelerate their deportation. According to a statement by Secretary Johnson, “the focus of this weekend’s operations were adults and their children who (i) were apprehended after May 1, 2014 crossing the southern border illegally, (ii) have been issued final orders of removal by an immigration court, and (iii) have exhausted appropriate legal remedies, and have no outstanding appeal or claim for asylum or other humanitarian relief under our laws.”

The guiding, but largely untested, assumption on which these strategies have been based is that Central Americans considering migration are misinformed about the risks and low probability of success such a journey entails—and when made aware of these facts, they will opt to stay home.

The critical question in assessing the underlying assumption of the U.S. deterrence campaign, then, is whether those individuals who knew the facts and dangers about migrating to the U.S. were less likely to consider migration as a viable strategy than those who were not as aware of those factors. Secondly, if awareness of the increased risk does not help explain who migrates from Central America, what does?

The Impact of Crime on Migration Intentions

In the spring of 2014, Vanderbilt University’s Latin American and Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) conducted a series of nationally representative surveys across the Northern Triangle countries that included questions about participants’ intentions to migrate, as well as whether they had been victimized by crime in the previous twelve months. While having an intention to migrate does not necessarily mean someone actually migrated, it does identify Central American residents who viewed migration as a viable option—precisely the people the U.S. government was targeting with the messaging campaign.

The LAPOP data suggest that those individuals who have been victimized by crime are considerably more likely to consider migration as a viable option than their non-victim counterparts. As we see in Figure 2, in Honduras, 28 percent of non-victims reported having intentions to migrate, while close to 56 percent of respondents that had been victimized more than once by crime in the previous twelve months intended to migrate. In El Salvador, only 25 percent of non-victims had plans to migrate compared to 44 percent of those victimized multiple times expressing intentions to migrate. Only in Guatemala did non-victims and victims of a single crime report migration intentions at a similar rate.

This relationship between crime victimization and migration intentions in Honduras and El Salvador remains strong even after controlling for an assortment of other factors. Again, only in Guatemala did crime victimization not emerge as a significant predictor of migration intentions—a finding that is perhaps not surprising given the steady decline in violence over the past several years in that country.

Figure 2. Crime Victimization and Migration Intentions, 2014

Source: LAPOP, AmericasBarometer 2014.

Awareness of Migration Dangers in Honduras

Clearly, Central Americans were considering their options in 2014 and, for Salvadorans and Hondurans at least, crime victimization influenced this decision calculus. But what did they know about the journey to the United States? A subsequent LAPOP survey of more than 3,000 Honduran residents provides a glimpse at their knowledge of the U.S. immigration climate in late summer of 2014. Though not nationally representative, the survey included residents across twelve Honduran municipalities with homicide rates ranging from 8.6 to over 200 per 100,000—allowing us to explore the determinants of migration intentions across different levels of crime and violence.

Respondents were asked about their views of the U.S. immigration context at the time of the interview (July-August 2014) compared to what it had been in 2013. From Figure 3 it is clear that by the summer of 2014, Hondurans were well aware of the dangers involved in migration to the United States and the increased chances of deportation. Nearly 86 percent said that they thought crossing the border was more difficult in 2014 than it had been twelve months earlier, 83 percent viewed the trip as less safe than in 2013, and almost 80 percent reported that deportations had increased compared to the previous year.

Figure 3. Honduran Views of Immigration to U.S., 2014

The survey was administered in the midst of the “Dangers Awareness Campaign,” suggesting that either this U.S.-funded media campaign worked as intended, or that most Hondurans already knew that migration to the United States was dangerous and had a low probability of success. In either case, it is clear that in Honduras, if not throughout Central America, residents were acutely aware of the risks associated with migration to the U.S.

The Role of Danger Awareness in Migration Intentions

Though the messaging campaigns appear to have succeeded in convincing—or reminding—Hondurans, and perhaps their Salvadoran and Guatemalan counterparts, that migration to the United States is dangerous and unlikely to succeed, this knowledge did not deter them from making plans to migrate. Further analysis of Honduran LAPOP survey respondents shows that knowledge of the risks of migration—deportation, border conditions, and treatment in the United States—played no significant role in who had plans to migrate and who did not have such plans. Based on the results of a multivariate regression analysis (a statistical technique that takes into account the effects of multiple factors on an individual’s intention to migrate), whether a survey respondent viewed migration to the United States as more dangerous, less dangerous, or about the same as it was in 2013 had no impact on whether or not that person reported intentions to migrate. Similarly, all else being equal, individuals who thought deportations had increased in 2014 were just as likely to report intentions to migrate as those individuals who thought deportations had decreased since 2013.

If awareness of the dangers involved in migration to the United States does not help explain who migrates and why, what does? Once again, the analysis of Honduran respondents reveals that among the most powerful indicators of migration intentions is crime victimization. The analysis offers concrete, systematic evidence of the relative weight crime victimization plays in the migration decision after controlling for the level of danger awareness and other factors such as income, age, gender, and whether or not the respondent reported receiving remittances (Figure 4).

The likelihood of a respondent reporting intentions to migrate nearly doubles for those who reported that they had been a victim of crime more than once in the previous 12 months, compared to those respondents who were not victimized by crime in that timeframe. The fact that such an effect emerges even after taking into account well-established predictors of migration intentions speaks to the important role that crime victimization plays in the migration decision of Hondurans.” As noted above, these findings parallel those found in our analysis of migration intentions in El Salvador as well.

Figure 4. Crime Victimization and Migration Intentions in Honduras

Conclusion

What do these findings suggest in terms of the effectiveness of the U.S. deterrence efforts and awareness campaign carried out over the past year and a half? First, it seems that the campaign successfully sent the message to residents of the primary sending countries in Central America that the United States will “send you back.” It is also clear that the trip north is perceived as being far more dangerous than it was in previous years, at least for Honduran survey respondents. After 18 months of concerted efforts by the United States and Mexican governments to dissuade Central Americans from making the trip, it is a safe assumption that most considering such a journey in the future are well aware of the dangers and low chances of success.

Yet Central American men, women, and children continue to make the trip. Between October 2015 and January 2016, CBP apprehensions of families and unaccompanied children in the southwest border increased more than 100 percent compared to the same period in the previous year. Why do these individuals continue trying to make the trip when seemingly fully aware of the dangers involved? The findings reported here suggest that no matter what the future might hold in terms of the dangers of migration, it is preferable to a present-day life of crime and violence. The unprecedented levels of crime and violence that have overwhelmed the Northern Triangle countries in recent years have produced a refugee situation for those directly in the line of fire, making no amount of danger or chance of deportation sufficient to dissuade those victims from leaving.